THE ROOTLESS - WE WHO REMAIN

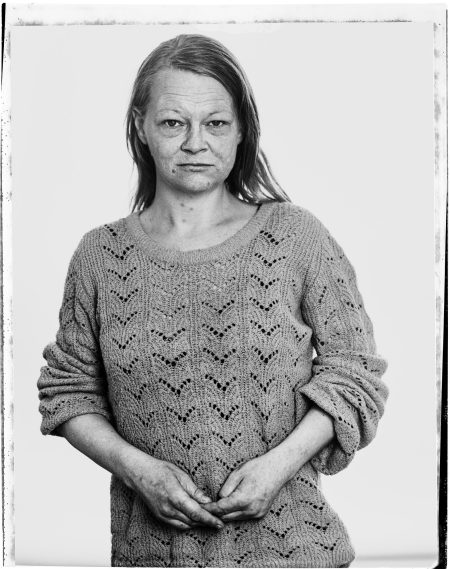

BETTINA BORREGAARD | 1980

The last 13 years of my life I have spent just trying to survive. I’m currently staying at my ex-boyfriend’s place in Kalundborg, because I was evicted from the subsidised housing I was borrowing from a friend. I still get my methadone, drink vodka and shoot up on the methadone once a week. That calms me down.

I don’t feel so good. The past few years have made me a lot older than I actually am. I’m 42 now, and I feel tired, and I have little scars on my arms and legs, so I never wear shorts. The only place I can shoot up now is the root of my thumb. My teeth aren’t doing too great either, I’m missing all the ones in my upper jaw. My ex-boyfriend who passed away a year ago beat me up and broke my ribs, and because of this I’ve been hospitalised several times. That’s why I don’t walk so well these days. I was with him at the hospital until the end.

I dream of getting housing, so I can stabilise myself and take better care of my cat. It’s black and called Kinte – like Kunta Kinte from Roots, which was my mother’s favourite TV-show. I’m going to try and go to the council. They must be able to help me somehow.

The Rootless – We Who Remain

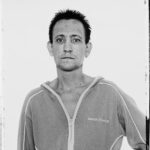

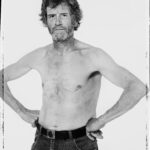

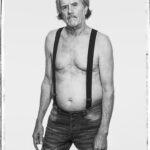

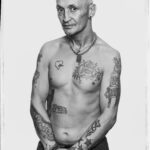

In the early winter of 2008, I walked through the streets and parks of Copenhagen and visited shelters and reception centres. Here, I met people who existed on the edge of life. People who were moving, tough, eccentric, hardened, tender and fragile, and who forced me to face a reality which I had preferred to know nothing about, but which intrigued me nonetheless.

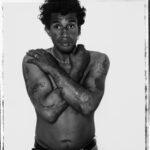

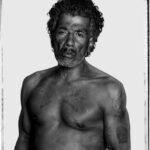

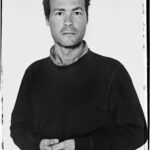

My meetings with these 30 homeless who had been pushed out of their homes and out of society became the beginning of the project called The Rootless. The result became a series of portraits that told the stories of the lives behind the faces we meet in the streets or in front of the supermarket. These were stories of people whose lives had been disastrously changed by unfortunate actions or conditions of life. The one thing that these people had in common was that they all lived on the street and were fighting their way through life one day at a time.

Thirteen years later, I’ve returned to find out what has become of the homeless, since I photographed them in 2008.

As a photographer, I’m interested in seeing how time affects the human body. How it’s reflected in a person’s face, and the traces it leaves behind. How does the passing of time shape us physically and mentally? And not just the homeless, but me as well, as my gaze has changed during the years that have gone by.

It has been a moving experience, tracking down those who remain. Far too many times, I’ve been told that the person I was looking for had died – either of an overdose, alcohol or suicide. Or that they were too sick to participate. The news of their fates affected me every time. The wasted opportunities. The lives cut short. Out of the thirty homeless I photographed in 2008, thirteen are no longer with us. Four are currently too sick to participate. Six have been impossible to find. Seven people I managed to trace and photograph again.

Inviting the homeless into my studio from the city benches and placing them in front of my camera transformed them. Sometimes the changes were subtle, other times surprising. There was always a transformation. They took themselves seriously with a strength I had not expected, and I’m moved by the way they felt seen as people – and not just as anonymous figures.

The studio became neutral territory. It wasn’t their familiar surroundings, and it wasn’t my home. Within this space emerged the opportunity for genuine contact. Without words, but through their posture, their gaze and focus, they were capable of communicating something essential that bridged the gap between two different worlds.

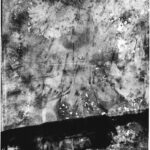

The Rootless – We Who Remain is a combination of my previous portraits from 2008 placed side by side with my new portraits of the homeless who are still alive today, and whom I have been able to trace. The dead are also represented with new photographs. The original negatives of their portraits were buried in the ground for several months and were then further dissolved through a chemical process. The transformed negatives have then been scanned and enlarged. These new portraits are now characterised by meaningful traces left by the passing of time in their absence as well as the disintegration of their faces and bodies. To me this captures the transitoriness of life and the much too short lives of the homeless.

Helga Theilgaard

Photographer